Tomorrow is Veterans Day in my country. It’s a national holiday, related to Armistice Day, Remembrance Day and Volkstrauertag.

I’ll be talking mostly about what’s happened since 1914, why I don’t fear the future, and what I think we can achieve if we use our brains.

It’s mostly history, with a little science. This isn’t the usual “science news” post:

- Looking back

- Moving forward

Remembering

It’s been an eventful century.

It’s been an eventful century.

Those photos show what was left of Pozières in 1916. The top one is a view of the village’s main street.

What happened there wasn’t all bad news.

Someone returned to the Pozières site.

The place was habitable, and inhabited. After folks filled in many of the craters, re-built the road and streets, and restored enough topsoil to make agriculture possible.

That’s good. But Pozières wasn’t just the way it was.

That’s inevitable. Change is among the few constants in this universe. In this case, folks made some good choices over the next century.

I hope that at least some of the folks living in Pozières could get out. But they, or someone else, did what humans do: recovered, rebuilt, and tried to avoid doing what went wrong last time.

ANZAC Day is another war-related holiday, in April.1

I think this ANZAC Day quote applies to the autumn remembrances, too:

“They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.”

(ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee)

Nearly a century later, some still remember. Considering what’s happened since, that’s not doing badly at all.

That image, taken from Google Maps, shows Pozières in the early 21st century.

Aside from a few architectural details and signage, it reminds me of many small towns where I grew up.

Land near Pozières isn’t nearly as level as what I was used to. And paved roads in the Red River Valley of the North are almost always raised, with deep ditches. It helps keep them clear after light snow, and helps us find them after heavier snowfall.

And that’s another topic. Back to the 20th century.

Hostilities ceased on the Western Front of the “War to End All Wars” at the “eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month” of 1918.

World War I may or may not be the most destructive war ever. It depends on which statistics you look at. By any reasonable standard, though, it was bad.

What with assorted genocides and impressively deadly weapons, about 6,000,000 civilians had been killed. I gather that the problem was, partly, less-than-precise weapons delivery tech. Smart these weapons weren’t.

Small wonder that some folks thought it was the end of civilization as they knew it.

“…Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world….”

(“The Second Coming,” W. B. Yeats (1919))

They were right.

The European and Euro-American glory days of the 19th century were gone. For good.

But we had a few good times during the 20th century. Happily, we also grew a little wiser. Enough of us to make a difference, anyway.

We survived another global war — or, in my view, the second phase of a conflict that started in 1914.

The mess started long before Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination set off a cascade reaction in Europe’s interlocking treaties. That’s a definite milestone, though.

Ironically, the treaties had been intended to prevent war.

Using Our Brains — Wisely

European leaders apparently thought they could avoid war by making the next one more cataclysmic than usual.

European leaders apparently thought they could avoid war by making the next one more cataclysmic than usual.

That’s why they crafted a web of treaties.

By the time they finished, pretty much all European countries would defend or attack each other if anyone started the sequence.

The idea goes back at least to 1870. We tried it again, after 1945; and got lucky. Or maybe enough leaders realized that they were on the front lines, like everyone else. Or meant what they said about wanting peace.

The 1870 theory was sound. In a ‘mutual assured destruction’ system, no rational leader would attack if the action would result in retaliation from other nations.

It would have worked in the early 1900s.

In a world where all leaders were completely rational.

That’s not what our world is like. Not even early-20th-century Europe.

There was more going on, of course. I’ve yet to run across a truly simple situation in humanity’s long story.

Since very strange notions about logic and faith, reason and religion get taken seriously, I keep repeating pretty much the same thing.

Using our brains is a good idea.

Using our brains is a good idea.

That’s not just my opinion. I’m a Catholic, so using my brain is a requirement.

That may take some explanation.

Because I’m human, I can think and decide what I do. (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 50, 1704, 1730–1731, 1778)

I could decide to not think, acting on whatever daft impulse comes along.

I’ve found that it’s easier than thinking, in the short run. It can even result in enjoyable experiences.

Long-term results are less than satisfactory.

Basically, each of us has a brain. We’re expected to think. (Catechism, 1762–1775, 1776)

I’ve talked about reason, emotions, and why it’s so hard to act reasonably. Even when we try. (March 5, 2017; March 5, 2017; October 5, 2016)

The “Peace to End Peace”

That’s what Wesel looked like in 1945. Another reason I don’t miss the ‘good old days.’

Names change as “now” moves through time. So do attitudes, often more slowly.

Somewhere in the 20th century folks in my culture started calling the 1914 through 1918 sequence of battles the World War, Great War, or War to End All Wars.

None of those names stuck, partly because chapter two of the “war to end all wars” started in 1939.

These days I mostly hear the 1914-1918 sequence called World War One or the First World War.

These days I mostly hear the 1914-1918 sequence called World War One or the First World War.

The “First World War” moniker dates to September 1914, when biologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel discussed what was happening in Europe.

He said it would become humanity’s first global conflict: the “First World War.”

He was right.

Calling it the “War to End All Wars” made slightly more sense when H. G. Wells wrote “The War That Will End War.” The book was published in 1914.

Wells blamed Europe’s Central Powers for starting the war. He had a solution, too: crush German militarism. That’s pretty much what the Allies tried, when the Central Powers ran out of things to be broken and people to be killed.

The ‘blame Germany’ strategy worked pretty well for maybe a decade. Longer, depending on what you look at. And how you define “worked.”

Not everyone agreed with Mr. Wells, or thought that punishing folks when their leaders lost a war made sense.

Even in 1914, a fair number knew enough about history and humans to realize that one conflict is ‘the war to end war’ only until the next one. Some even thought post-war punishments should be vaguely reasonable.

Someone, somewhere, may still call World War One the War to End All Wars without being cynical, sarcastic, or worse.

I think a British staff officer was closer to the mark in how he saw what the Allies were doing at Paris, and called it the “Peace to end Peace.”

Apparently quite a few experts still say that the Treaty of Versailles was pretty much a good idea.

Apparently quite a few experts still say that the Treaty of Versailles was pretty much a good idea.

France, the story goes, was ever so lenient and restrained in how Germans were punished for losing the war. Not that experts put it quite that way, of course.

I don’t think anyone who was involved came out Versailles smelling like a rose. Particularly the folks running that show.

One of these days I’ll dig into just how restrictions on German industry, research, and related activities affected that country.

I don’t think it helped that 15.1% Germany’s active male population was dead when Versailles was signed.

A severe global economic downturn my nation calls the Great Depression started about a decade later. It affected everyone, not just Germany.

Americans generally saw it mostly from our country’s viewpoint. So did many Germans.

Germans had a few more reasons to complain.

Some, not all, felt an understandable — my opinion — lack of appreciation for what had been done to their country’s economy by the winners.

I’d better clarify that.

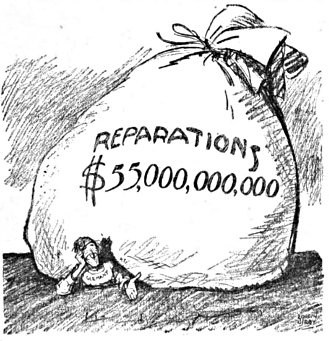

I can see how Germans might not appreciate being forced to pay exorbitant tribute — what we call “reparations” these days — while being forbidden to make ‘bad’ things, or seek ‘forbidden’ knowledge.

Particularly, in the latter case, when the folks who demanded tribute saw no reason to stop building the same tech while pursuing ‘forbidden’ knowledge.

Being upset in circumstances like that is, I think, reasonable. But not all possible reactions make sense. Or are, by any reasonable standard, good ideas.

By the early 1930s, Germans were feeling economic hardships, like almost everyone else.

Add that to already-potent resentment of Versailles restrictions, stir vigorously with a highly effective orator, and you get Nationalsozialismus. That’s a vast oversimplification, and yet again another topic.2

Or maybe not so much.

What I think about it is — a bit complicated. I’ll talk about that another day.

Learning: Slowly

The decades since 1945 haven’t been exactly peaceful.

The decades since 1945 haven’t been exactly peaceful.

They could have been much worse, though. Many national leaders have acted as if they don’t want to start World War III.

We’ve endured lots of little wars. Most of which were probably avoidable. But nothing even close to the sort of thing popularized in “The Day the Earth Caught Fire” and “Dr. Strangelove.”

I’m not sure how many folks took melodramatic romps — with or without atomic zombies and giant mutant frogs — and their more dignified siblings seriously. Still more topics.

The last 72 years haven’t been perfect, but we seem to have learned a little.

European nations have refrained from slaughtering each other’s civilians for decades. That’s very remarkable, given the region’s history.

Government-level shenanigans have stayed pretty much the same, I think. At least in America.

The details are different, of course. I haven’t heard “communist menace” or “creeping socialism” for years. Now it’s climate change and gun control.

It’s like the song says: “You Say ‘Tomato’, I say ‘Tomato’…” Sort of. The Astaire-Kelley duet is in a YouTube video, about five and a half minutes long. Song and dance on roller skates: loads of fun.

We survived both phases of the 20th century global conflict.

And we’ve learned a bit.

The Allies didn’t, quite, repeat the blunder they’d committed after phase one.

Germany ended up in two pieces. But folks in the western half weren’t punished to the point where they’d flee to the east.

Also, happily, many or most Germans were horrified by their government’s efforts to purge Lebensunwertes Leben from humanity’s gene pool. Among other things.

I get the impression that nobody except a few crackpots yearn for those days of yesteryear. Or will admit it, at any rate.

Eugenics’ public relations problems affected my country, too. It took several decades for folks who want a better — by their standards — humanity to rehabilitate their goals.

Repackaging their efforts to purge the world of folks like me as supporting ‘quality of life’ was, I think, brilliant marketing.

Repackaging their efforts to purge the world of folks like me as supporting ‘quality of life’ was, I think, brilliant marketing.

I don’t approve, partly because I’d probably be culled soon after the first few categories of defectives were processed. And that’s — you guessed it — another topic.

The good news, as I see it, is that it’s been such a struggle to re-establish eugenic ideals. Having pretty much the same thing resurface with new slogans, not so good.

But I think there’s reason to hope that more folks are learning that all humans are people.

My country’s ruling class losing their former control of what we can learn helped. My opinion. I don’t miss the days when most saw the world through traditional information channels, or not at all.

As I keep saying, folks learn. Slowly, but we do learn.

Some of us even developed an alternative to the old empire-collapse-rebuild cycle. It’s been working, far from perfectly, since 1945. (October 30, 2016)

Science and Wisdom

Scientists have been learning a great deal. And, I think, developing a little wisdom.

Scientists have been learning a great deal. And, I think, developing a little wisdom.

And it’s not the “wisdom” to turn away from science and suchlike wickedness, lest an irritable Almighty smite us mightily.

The ‘science is bad’ attitude, adapted to a groovier outlook on life, got more traction in the 1960s.

That’s another attitude I can understand, but do not share.

I never considered emulating the ‘hippie’ philosophy and way of life.

On the other hand, many of their concerns and hopes made sense to me. And still do.

Maybe it seems odd, a Christian saying that peace, love, and cherishing nature is anything but a Satanic snare or commie plot.

The explanation is pretty simple. I’m a Christian who eventually became a Catholic. I’m still Christian: and signed up with an outfit that’s not tied to one culture or era. The Catholic Church really is καθολικός. (October 30, 2016; July 24, 2016)

Our version of respecting nature, recognizing humanity’s “transcendent dignity,” and working for social justice, makes sense. (Catechism, 373, 1928–1942, 2402)

We’re not told that God has anger management issues and values ignorance.

Which brings me to an example of that wisdom I mentioned.

Which brings me to an example of that wisdom I mentioned.

In my youth, prospects for large-scale weather control looked very hopeful. We may have the technology now.

One reason we don’t prevent weather disasters is that field tests stopped in the early 1970s. As far as I know.

I think that was prudent. Not because I fear the folly of “tampering with things man was not supposed to know.” (June 23, 2017)

Scientific research is a good idea — provided that we don’t chuck ethics because ‘it’s for science!’

We’re supposed to keep learning how this universe works.

I’ve said it before, and probably will again. Science and religion get along fine. At last for Catholics who understand our faith. (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 159, 214–217, 283, 294, 341)

Like I said, We may already be able to change weather on a local-to-regional scale.

Precision control is a serious issue. And not yet resolved.

Safety protocols for experiments involving hurricanes changed after a scary coincidence in 1947. An altered hurricane made a U-turn.

Then it hit parts of Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. Property damage was only $3,260,000. The death toll was incredibly low: one person.

I think it helped that scientists saw where it was headed.

Also an increasing government awareness that the hoi polli aren’t particularly prone to panic. (September 1, 2017; August 11, 2017)

Later analysis of the 1947 experiment suggests that the hurricane turning around wasn’t entirely due to human actions. Scientists kept the new protocols, anyway. Just in case.

The next major scare came a few decades later. American courts finally decided that scientists who had modified a storm in South Dakota weren’t legally responsible for the death and destruction which followed.

There wasn’t enough evidence. ‘After that therefore because of that’ isn’t enough to convict. Usually. American scientists were even more careful after the 1972 incident. (September 10, 2017)

Let’s Not Do That Again

I can’t see World War I as all good or all bad. Or even necessary, in 20-20 hindsight.

That doesn’t make me a dove. Or hawk. (January 22, 2017)

Happily, a remarkable number of folks survived both global phases of the 20th century’s wars.

We even had enough survivors to rebuild most of what had been destroyed. A few generations after 1945, most of the physical damage has been repaired.

Both/all sides had somehow failed to obliterate quite a few libraries, museums, and culturally-significant structures.

That’s good news.

So was what some survivors, digging out of occasionally-radioactive rubble, thought about going through the same thing. Again.

Many decided that they’d had enough of humanity’s empire-collapse-rebuild cycle.

I think preserving a remarkable number of documents during the post-Ancient ‘rebuild’ phase helped. Knowing about past mistakes, and successes, can help folks make better decisions. If we pay attention. (May 28, 2017)

Good Ideas

I also think some Enlightenment-era ideas made sense. Basically.

I also think some Enlightenment-era ideas made sense. Basically.

Seeking knowledge and avoiding state-sponsored religions makes sense.

Other ideas don’t. I can sympathize with the still-fashionable notion that religion and superstition are the same thing. But I don’t agree. (October 27, 2017)

I think today’s situation looks a bit like the Enlightenment. Back then, surviving Europeans were recovering from the Thirty Years War.

Today we’ve repaired most of the physical destruction from the previous century’s global wars. Or war, as I suspect historians will eventually see the 1914-1918 conflict and its 1939-1945 continuation.

We’re still dealing with psychological and social issues triggered by the war. With mixed success. My opinion.

Many Enlightenment-era folks thought going through something like the Thirty Years War again would be a bad idea. I think they were right. (November 6, 2016)

‘More of the same’ wasn’t an acceptable option.

It’s just shy of 370 years since the Thirty Years War ended. I don’t know when we started using that name. Not exactly.

Like I said, names change. Folks living 370 years after the end what we call World War II will almost certainly have another name for it. I don’t know what it’ll be.

Maybe some will call the 1914-1945 conflict the Colonial War when 2315 rolls past.

I’m not the first person to call it that. My father suggested the name, somewhere around 1970. His interests, habits and quirky mental processes were much like mine, so likely enough he’d run across the idea somewhere. Or its component pieces.

Maybe he noticed the probable motives behind both phases — merging an adjective and noun to get a new name.

Taking the Long View

A half-century after I first read them, these lines by Tennyson are still among my favorite bits of poetry:

A half-century after I first read them, these lines by Tennyson are still among my favorite bits of poetry:

“…For I dipt into the future, far as human eye could see,

“Saw the vision of the world, and all the wonder that would be;…

“…Till the war-drum throbbed no longer, and the battle-flags were furl’d

“In the Parliament of man, the Federation of the world.

“There the common sense of most shall hold a fretful realm in awe,

“And the kindly earth shall slumber, lapt in universal law….”

(“Locksley Hall,” Alfred, Lord Tennyson)

I’ve since realized that “the common sense of most” still needs improvement. Or encouragement. How I see being “lapt in universal law” — is complicated.

But I haven’t stopped thinking that we can build a better world than today’s. And that wistfully imagining a return to some illusory Golden Age isn’t practical. Neither is grimly clinging to the status quo. Change will happen.

Which direction it takes us largely up to us.

We can decide to try building a better world.

It’s a huge job. It means cooperating with everyone who will keep what has worked in the past: and change what hasn’t. Everyone. Not just ‘folks like me.’

Our efforts also, I am convinced, won’t see significant results for centuries, probably millennia. I see that as something to accept, and keep working anyway. It’ll be worth it. In the long run.

Building a Civilization of Love

We’ve made some progress over the last few millennia. I think the Code of Hammurabi and United Nations Charter were improvements on what we’d had before.

We’ve made some progress over the last few millennia. I think the Code of Hammurabi and United Nations Charter were improvements on what we’d had before.

And I am convinced that they’re not perfect.

Whatever we’ve cobbled together by the time those documents seem roughly contemporary won’t be perfect, either.

But I think we can build a world that’s better than today. I am convinced that we must try.

I think St. John Paul II is right. The future looks — hopeful. If enough of us decide that peace, solidarity, justice, and liberty make sense. And we’re willing to do something about what we believe.

“…In this sense the future belongs to you young people, just as it once belonged to the generation of those who are now adults…. …To you belongs responsibility for what will one day become reality together with yourselves, but which still lies in the future….”

(“Dilecti Amici,” St. John Paul II (March 21, 1985))“…The answer to the fear which darkens human existence at the end of the twentieth century is the common effort to build the civilization of love, founded on the universal values of peace, solidarity, justice, and liberty….”

(“To the United Nations Organization,” St. John Paul II (October 5, 1995))

Somewhat-related posts, my opinion; your experience may vary:

Somewhat-related posts, my opinion; your experience may vary:

- “London: Death, Hope, and Love”

(June 4, 2017) - “‘The Federation of the World’”

(May 28, 2017) - “More Than a 3-Day Weekend”

(May 28, 2017) - “Remembering Armistice Day”

(November 11, 2016) - “Authority, Superstition, Progress”

(October 30, 2016)

2 We’ll learn from the past, I hope:

- Wikipedia

I don’t see any hills, or much in the way of buildings, in the more recent picture of Pozières.

Stutter: at the the “eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month”

Extra article and missing word: “Wells blamed the Europe’s Central Powers starting the war.”

Missing word: “involved came out Versailles smelling like a rose.”

Another missing word: “awareness the hoi polli aren’t particularly prone to panic.”

The Friendly Neighborhood Proofreader

🙂 Thanks!